So when a friend reminded me of Josephine Tey's books, I read the three preceding books in her Inspector Alan Grant series... and then I re-read The Daughter of Time again. It's been a while since I've read mysteries without a female protagonist, but Tey's Inspector Grant series is an enjoyable police procedural mystery set, peppered with descriptive piquancies - perfect for gray Northwest evenings!

In the first three books, Inspector Grant is in the field, running around Britain solving murder mysteries and gaining insights into human behavior from his theatre and society friends. But in the last, while recuperating in hospital from an injury sustained while chasing crooks, he "solves" the mystery of whether or not Richard III murdered the Princes in the Tower. (He comes to the conclusion that he did not, and that the hunchbacked, throne-usurping Uncle Richard story was propaganda put out by Henry VII and enshrined by pro-Tudor factions for decades onward. Even Shakespeare was not blameless, writing as he did under a Tudor monarch.)

Of course, reading the series reminded me that earlier in the year, DNA tests proved that a skeleton found under a car park in Leicester was indeed Richard III's.

Meanwhile, an ocean and several hundred years (and light years) away, I am also fascinated by the superhero film genre as an ever-evolving expression of national identity. So when Man of Steel came out earlier this year, I went to see it. (It's a pretty crappy movie. Amy Adams is wonderful as always, and I did like the extended back story of Jor-El and Krypton. But there were way too many gratuitous explosions and overly long scenes of the casual destruction of planets and buildings. The tornado scene was particularly unfortunate, given so much devastation this year in Oklahoma. How can a superhero save an audience that is too desensitized to violence?)

Looking at oh-so-pretty Henry Cavill was basically the only thing that kept me in my seat for over two hours.

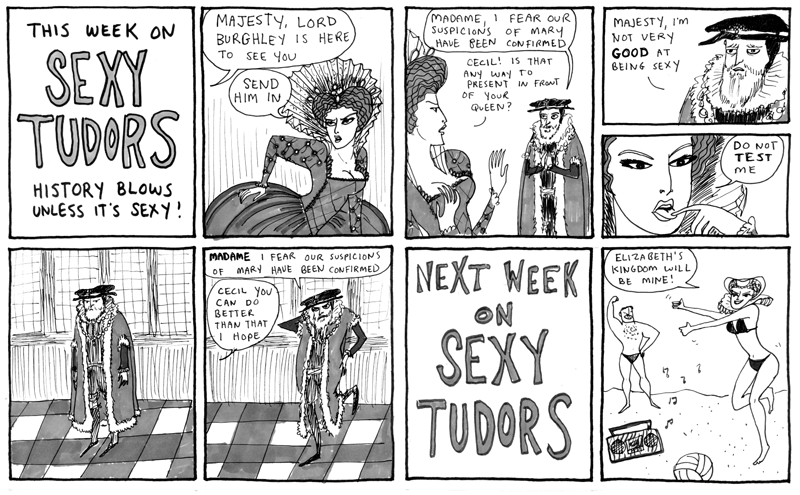

Soooo, after election season settled down I finally got around to watching The Tudors.

I had long been personally boycotting the series due to the anti-Plantagenet conspiracy that particular dynasty wreaked on its predecessors (see above and what reading The Daughter of Time did to an impressionable 12-year-old).

Turns out, the series is brilliant. It takes a lot of liberties with the timeline (and some historical figures age quickly, while others don't age at all in what should be a 20-year span). But aside from some digressions from the history books and chronology, I think it gets the general spirit right.

Trying to make a rather fit Jonathan Rhys-Meyers look like a rotund Henry VIII, though, was amusing, as was Henry telling Thomas More "You're not a saint!" (Ha ha... )

The most fascinating aspect of the series, though, was how it portrayed the tumultuous break with the Church in Rome and the rocky, somewhat sketchy beginnings of the Church of England. I really appreciated how the series included the doctrinal implications of the schism as well as the cultural and political ones. That gray, confusing area where England was neither fully Catholic nor very Protestant is generally glossed over, but is so fascinating... especially from an organizer's perspective! (What do we do with all these abbeys? What do we believe about the transubstantiation, again? How do we tell the illiterate masses what just happened? What is happening? What's the definition of heresy this week?)

The series is most known not for its insightful theological statements, of course, but for its raunchy soft-core porn-esque sex scenes.

From the brilliant and nerdy comic Hark! A Vagrant:

Maybe I should just continue on this chronological journey, and move on to the Stuarts! Mi Hermana did tell me over Thanksgiving that she's addicted to Game of Thrones, and that after recognizing threads from family rants while watching the Red Wedding episode, discovered it was indeed based in part on the Glencoe Massacre...